In 2020, the Detroit Continuum of Care (CoC), the Detroit Advisors Group, the Homeless Action Network of Detroit (HAND), the City of Detroit’s Division of Homeless Services (HRD)(1), and the local Veteran’s Administration (VA) partnered to reimagine what it looks like to be ending homelessness in Detroit, focused on the pursuit of housing justice.

Pursuing housing justice requires transformation: a new approach to housing instability and homelessness that is centered on racial equity, co-designed with people who have experienced homelessness, and built on a shared understanding of how Detroit’s homeless response currently perpetuates inequality and exclusion.

When reconciling a history of structural racism, marginalization, and harm is the question, housing justice is the answer. Structural racism is an underlying driver of homelessness in the United States. The high rates of poverty in Detroit, particularly among Black Detroiters, along with the city’s ranking as the most segregated city in America, are products of intentional choices and decades of corporate decision-making controlling the lives and livelihoods of the city’s residents, leaving many marginalized and cut off from opportunity.

There are inextricable linkages between housing, health, employment, and education, among other systems of care. Without recognizing these necessary linkages, housing justice will remain out of reach.

It is in recognition of these truths that the CoC Executive Committee, with the financial support of the McGregor Fund, engaged the National Innovation Service (NIS) Center for Housing Justice to support a community-driven process to define what housing justice means for Detroit and, from there, chart the path to a system rooted in justice. A path forward to transform Detroit’s citywide response to homelessness is outlined here in the seven actions of Detroit’s Housing Justice Roadmap.

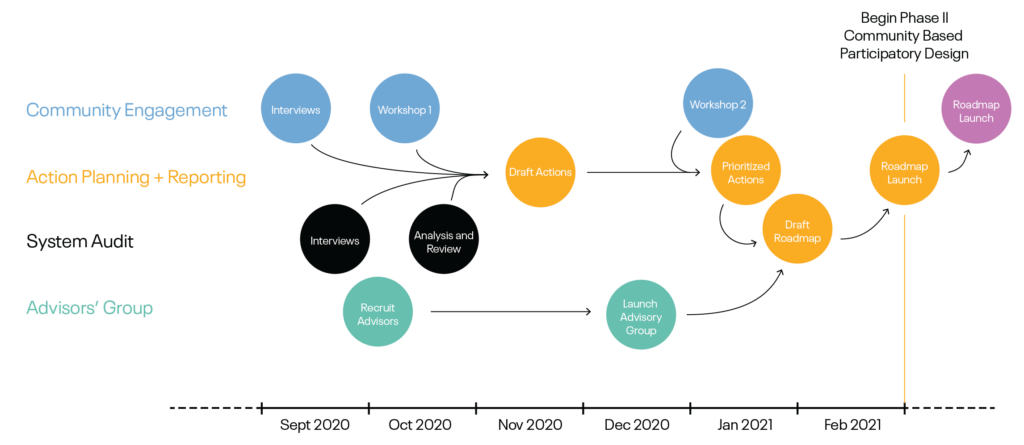

Detroit’s Housing Justice Roadmap is a product of deep community engagement and policy analysis. The community engagement process included more than 30 interviews with community organizers and advocates outside of the traditional homelessness services sector and homeless services administrators and providers. The process also included two community-wide workshops to engage the broader community working to address homelessness and a group of advisors comprised solely of Detroiters who have experienced homelessness. These advisors have been integral in guiding community engagement and refining the resulting analyses.

Policy analysis was conducted through a systems lens, evaluating the policies and structures identified through community engagement to understand what drives and perpetuates the community’s response to homelessness. This systems audit included an analysis of pertinent federal, state, and local policies, procedures, and data to understand what underpins the dynamics of housing instability and homelessness in Detroit that members of the community described. A more detailed description of the community engagement and systems audit are outlined below.

The community engagement process began with:

- More than 30 interviews, focused on understanding stakeholders’ vision for transformation, as well as roles within the current service arena, and observations on housing and homelessness barriers across Detroit, and

- Community-led analysis to synthesize and dissect the themes that were explored in interviews, focus groups, and workshops with the broader community.

The 8-person Detroit Advisors Group has met on a regular basis since October 2020 to:

- Partner in the discovery process, action planning, and eventual co-design of the implementation of the Housing Justice Roadmap,

- Grow the coalition of co-designers alongside CoC and City partners, and

- Ensure that the priorities of those most impacted by homelessness and housing instability in Detroit are centered and represented throughout the process.

The Discovery Workshop was held in October 2020 with more than 120 members of the community to:

- Offer a preliminary diagnostic readout of community engagement and systems audit findings to-date,

- Ensure alignment behind the main themes identified in those interviews, and to

- Coalesce around major themes:

- Lacking systems-level connections across homeless services;

- Inadequate accountability to people experiencing homelessness;

- Lacking unified leadership and vision;

- Limited power-sharing; and

- Closed decision-making circuits.

The Roadmap Workshop was held in February of 2021 with more than 60 members of the community to share:

- A final synthesis of community engagement and system audit findings,

- Background on how those findings led to the seven actions, and to

- Gather feedback and input from community members on those actions and the community-driven path forward.

The systems audit began with:

- Short-term targeted technical assistance to support HRD in prioritizing federal COVID-19 relief funding,

- Policy and data analysis to understand gaps in Detroit’s homelessness response exacerbated by the pandemic, and

- Facilitating members of the CoC Executive Committee and HRD leadership in understanding the gaps in services that were identified and the funding needed.

- This process led to 18 interviews with funders and administrators, focused on understanding decision-making power dynamics, leadership and vision, and accountability across homeless services broadly.

NIS structured this engagement to position the Housing Justice Roadmap as the first of a three-phase process to begin transforming Detroit’s response to homelessness and move towards a system rooted in justice.

NIS recommends that, upon receipt of the Roadmap and the conclusion of Phase I, the CoC and HRD jointly launch a community-based participatory design process to co-design the implementation of the actions outlined here in the Roadmap.

The co-design phase is a 12–18-month process to bring in a diverse set of stakeholders, including people with lived expertise, providers, administrative leaders, community organizers, and advocates and map the path forward. Co-designing offers the opportunity for the community to prioritize and sequence the actions outlined in the Roadmap and develop the implementation plan for the CoC and HRD.

The third phase of work is the longer-term process of implementing the Roadmap actions and strategies based on the process designed with community stakeholders in Phase II. During this phase the community stakeholders would remain engaged to hold the system accountable to enacting the process and strategies as they will be co-designed, and moving toward justice.

The COVID-19 pandemic precluded the NIS team from traveling to Detroit for this initiative. This prevented the team from speaking with a wider array of frontline staff across programs and prevented the team from seeing the work of local homeless response programs in action. NIS attempted to address this limitation by engaging frontline staff in two community workshops, but deeper engagement with frontline staff will be necessary in future phases of this work.

Similarly, NIS methodology usually includes on-site workshops and meetings with larger groups of stakeholders working across the homeless response, but this was not possible due to pandemic restrictions. Provider agency leaders, middle management, and frontline workers were invited to and engaged in the community workshops. However, NIS recommends that the CoC and HRD engage more provider staff at every level in the review of the Roadmap and in deciding to move into the next phases of the work.

Lastly, given the amount of engagement and system audit necessary to understand homeless response programs in Detroit and the need to start with the foundational work of understanding how to build a system across the CoC and HRD, there was only minimal engagement of affordable housing and homeownership stakeholders. NIS did interview several programs and advocates and included a deep policy review of affordable housing and homeownership in order to address this limitation, but the CoC and HRD will need to broaden engagement with these stakeholders moving into co-design.

The National Innovation Service approaches systems transformation through the lenses of systems thinking and anti-racism. We center race and identity in our research methods and analysis, understanding that structural racism is at the foundation of America’s public systems and social failures. We therefore privilege the voices of those who are most vulnerable to the issues at hand, amplify the insights and experiences of Black, Indigenous, and Brown people, and ensure that communities and individuals who are most proximate to the issues are leaders in developing the analysis as well as the solutions.

Equity-centered systems transformation requires that we grapple with the root causes of homelessness but design toward a future where those who have historically been marginalized are supported in thriving. Our work is done through anti-oppression and anti-racist frameworks.

To envision housing justice, Detroiters must reckon with and honor the full history that has brought the city to its present-day victories and injustices.

The land known as Detroit was first Bkejwanong, a transitional village and hunting site for the Anishinaabe peoples, “a ‘junction of the continent’s major watersheds’…served as a hub of ancient indigenous travel and trade.”(2)

The groundbreaking work of Dr. Tiya Miles inThe Dawn of Detroit outlines this history, revisiting and correcting the city’s origin story. The history of injustice on this land, as Miles chronicles, dates back to wars inspired and backed by French colonizers, the expansion of the fur and animal trades, and the French enslavement of Indigenous people.

As the land traded hands from French to British colonizers and finally to the white, slaveholding founding generation of the United States, Miles writes that “greed, graft, and forced racialized labor” made up the cultural and industrial roots of Detroit.

The earliest phases of slavery in Detroit exploited the region’s Indigenous peoples, but racial categories positioned even enslaved Indigenous people above the few Black slaves in Detroit. Black men’s physical labor was used to fuel the fur trade while Black women were first exploited in Detroit for their sexual labor.(3) Today, sex work remains the only reliable work for many Black trans women in Detroit, illustrating the deep connections between the original social structures of the city and its present-day failures.

While the Revolutionary and Civil Wars slowly forced and led more Black people to Detroit, the Great Migration and the industrial demand of World War II offered Black Americans a promise of opportunity in Detroit. Its population boomed. Paired with that opportunity, however, were the foundations of structural racism, waiting to greet each new Black Detroiter.

Detroit’s neighborhoods weren’t segregated from the start, but white Detroiters confined Black Detroiters early in the Great Migration by first refusing to sell their homes to Black people and eventually through racially restrictive covenants and redlining.(4) Later, racism exacerbated postwar economic pressures and housing shortages in the city, leaving Black Detroiters segregated to the Lower East Side with substandard, overcrowded housing options.

In 1948, the Supreme Court ruled that racially restrictive covenants were unenforceable by law, a case made in part by Detroit’s own Orsel and Minnie McGhee. But government-backed redlining soon replaced restrictive covenants, effectively barring African Americans from homeownership and the accumulation of generational wealth. Through the middle of the 20th century, Black Detroiters only had access to substandard, crowded housing in segregated neighborhoods until Detroit’s white population began to move to the suburbs in the 1950s, taking resources, opportunities, and the tax base with them in what became known as white flight.

Structural racism stifled Detroit. The ensuing decades brought industrial decline, employment discrimination, and exploitation that starved the city’s residents of resources and services. Outsized property taxes were leveraged on the majority Black population to fill the local budget gap left by white flight. Those taxes then drove the city into decades of foreclosures, evictions, and home abandonment. The War on Drugs funneled much of those taxpayer dollars into law enforcement and the criminal justice system in the 1980s, resulting in high rates of over-policing and criminalization.

The Great Recession and Detroit’s 2013 bankruptcy filing exacerbated and perpetuated a century of housing injustice in the city.

Housing policies and market-driven local initiatives have failed generation after generation of Black Detroiters. To pursue its vision for housing justice, the community must assume a posture of proactively countering gentrification. Though local plans commit to “ensuring that those who have remained in Detroit benefit from its resurgence” and downtown Detroit is “revived,” a myriad of local policies and public-private partnerships are failing to the needs of most Detroit residents.(5)

Prior to the pandemic, homeowners were struggling with low home values, high-cost repairs, low rental income, and high property taxes. Rates of homeownership were sinking rapidly in Detroit and Michigan as a whole.(6) Renters had few housing options that were safe, maintained, and affordable to low-income households. At least one percent of the population was experiencing homelessness at any given time, while literal countless others experienced housing instability and couch surfing or doubling up with other households.

As we see across the country and in Detroit specifically, the COVID-19 pandemic is worsening each of these dynamics and more, further compounding the impacts of decades of structural racism.

Deep histories flow beneath present inequalities, silent as underground freshwater streams…Detroit is not the scene of natural disaster, but rather the scene of a crime–a crime committed by individuals, merchant-cabals, government officials, and empires foaming at the mouth for more.

Tiya Miles, The Dawn of Detroit: A Chronicle of Slavery and Freedom in the City of the Strait

However, Dr. Miles reminds us of the brilliance and resilience of Detroiters at another point in history: “One of Detroit’s prominent slaveholders once called the city ‘ruined,’ and yet, from the vantage point of Detroit’s most vulnerable residents in his time—enslaved men and women—disarray meant the opportunity for reinvention.”

Emancipatory action in our time, too, might be waterborne–ferried by the physical waters that embed social power, fed by the underground stream that is history. On the borderlands of bottom-line globalization, capitalistic expansion, and postindustrial flux, recognizing the historical links between land-seizers and body-snatchers, and exposing the tools and techniques of bondage as well as liberation, are incremental but purposeful ways to make room for visions that see the earth and all of its creatures free.

Dr. Tiya Miles

The National Innovation Service (NIS) partners with governments across the country to engage in systems-level transformations. We do this by creating collaborative coalitions between communities, public sector partners, and other relevant stakeholders to redesign systems with those most impacted at the center of decision-making processes. Our work is to build new systems that produce equitable outcomes.

Our team draws on a variety of disciplines and experiences to deliver this work, privileging direct experience of the problems we address and merging practices from service design, policy analysis, systems thinking, community organizing, and change management.

We develop strategies and roadmaps for transformation and also remain committed partners throughout implementation. As we establish and test pathways forward with our partners, we are working to advance equity-based policy and legislation at the local, state, and national levels, as well as the development of new models, products and social services.